/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23026044/bbkingliveregal.jpg)

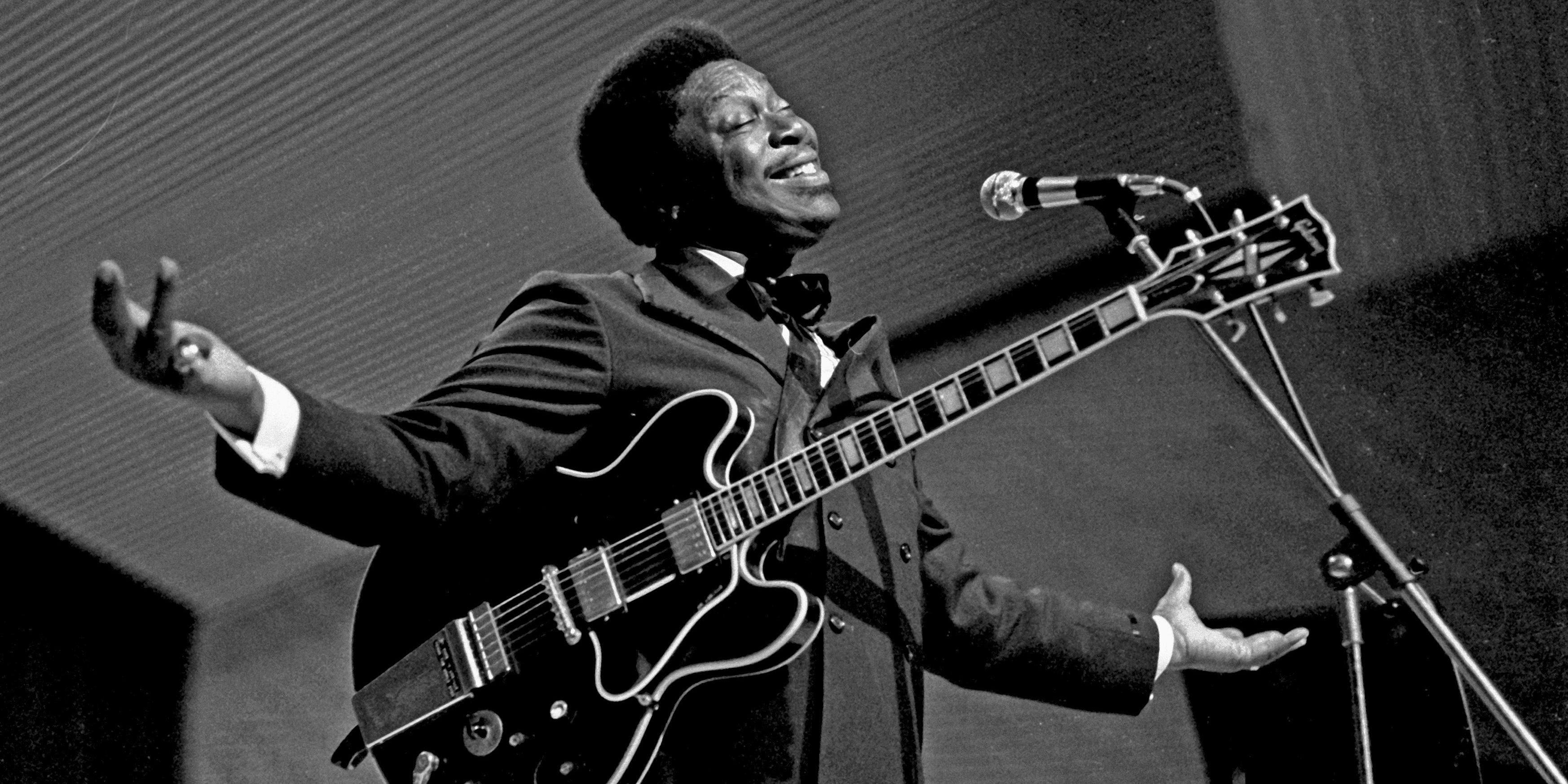

King’s parents separated when he was only five and his mother took him to live in the nearby hill country in Kilmichael, Mississippi. King was born to a family of poor sharecroppers on a plantation near the small town of Itta Bena in the Mississippi Delta. King was the heaviest of them all.Riley B. An attempt heard so many times on so many B.B. King records, a guitar tone like ancient bells, both plaintive and bouncy, revelling in sex and booze while plunging into broken-hearted despair.īut dead men are heavier than broken hearts, as the feller said, and B.B. King, “singing the blues is like being black twice.” This is music weighed down by the violence of centuries, yet it always pours forth intimately, ever “an autobiographical chronicle of personal catastrophe expressed lyrically”, according to Ellison, an attempt to transcend a brutal experience by “squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism”. Or, to put it as Billie Holiday put it, there’s the happy blues and the sad blues. The blues speak simultaneously of the comic and tragic aspects of the human condition, and particularly of the shared black American condition. sing it, “When I first got the blues, they brought me over on a ship/ Everybody wanna know why I sing the blues/ Well, I’ve been around a long time/ I’ve really paid my dues.” They tell the story of the black man’s path from slavery to citizenship, as LeRoi Jones once wrote. King played, it was just the cold hard truth - like hearing Martin Luther King speak.” The blues are indeed a constant recording and performance of black history, and they bare all - Middle Passage desolation, slavery and racism, poverty and heartbreak, good women and bad moonshine (or bad women and good moonshine). played a lot of the blues (200 shows a year on average 342 in 1956 alone).

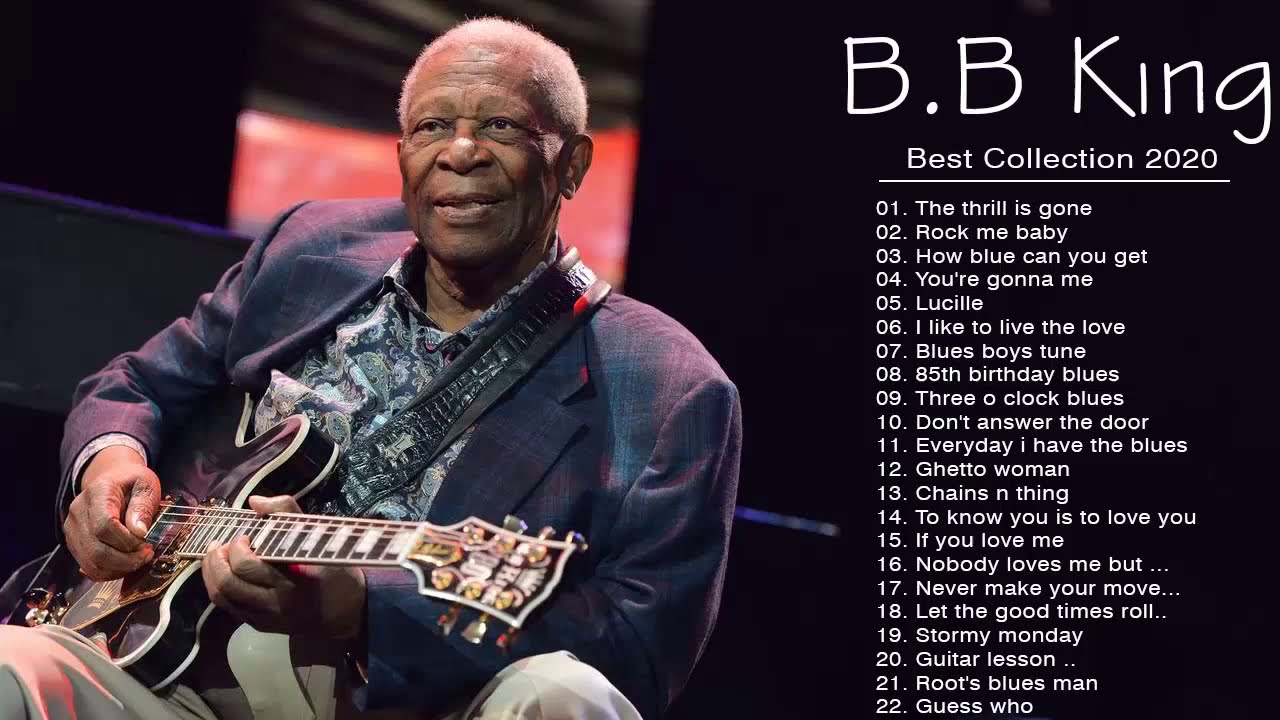

The blues might just be the most sophisticated and all-encompassing mode of storytelling in African-American culture, and B.B. King, he told a heck of a lot of stories. Genial, graceful, and “always a sweetheart,” as the guitarist Derek Trucks said of him. And he moved a lot, doubled up in laughter, grinned and shook his head, stopped in the middle of songs to tell old-timey stories. always did like his suits, three-piece salmon suits with pink patterned shirts, plaid suits and chequered suits and suits in bright pastel shades with extravagant trim.

King, he was wearing a shimmering golden tuxedo which, in comparison, made the spectacular Fox Theatre in Detroit, with its starburst and cartouches, its Moorish arches and vermilion columns, its Wurlitzer organ and plaster lions, look like an empty parking lot on a rainy day. “But none of us will ever be able to duplicate his tone, his choice of notes, his way of bending the strings.” ’Twas ever thus.

shows for so long that he remembers seeing him play half his shows standing up). (Bryan the friend is a guitar cat who’s been going to B.B. “I spent hours every single day when I would get home from high school playing along to his records trying to sound like him,” my friend Bryan told me. “I can get a little Frank, Sammy, a little Ray Charles, a little Mahalia Jackson in there,” talk-sings B.B. Lucille, after all, is immortal, her methods supernatural. Lucille - or, rather, the Lucille I saw him play that night, one of a succession of Gibson guitars - was stolen a few months later, only to resurface a few months after that in a Las Vegas pawnshop.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)